What a white face

The case for a United Nations of cultural data

My parents have moved house twice since I left Shanghai, so when I arrived at their flat last month I wasn’t expecting anything to feel familiar. But I was wrong. The apartment they moved into post-covid is down the same lane, next to the same rare inner-city petrol station, as the first house I really remember living in. I walked into the lòngtáng past the same outdoor laundry racks, metal exercise equipment and the entrance to my childhood home, before taking a right turn into their new building.

The level of familiarity is hard to explain.

I devoured books as a kid, and every world I entered through them had traces of my own world in it. I didn’t just live here, I set other people’s lives here. The lines have become so blurry I can’t actually remember if it was me who ran through that narrow shortcut over there or a character I can’t recall the name of.

The sameness is comforting but also eerie, as so much of the city has changed. Just one block over is a seven-storey mall, attached to two 30-ish-storey office and residential towers. When my family moved to Shanghai, in the late 90s, that same space was occupied by market stalls, exclusively ground-level, selling fake Beanie Babies and Abercrombie and Fitch polos. The hawkers were all long gone by the time I left in 2010 (they’d upgraded their stock and moved to an air conditioned building across town), but I was still taken aback by something I can only describe as concrete-jungle-shininess, which now defined the space.

Still, the energy of the city felt more like the Shanghai I knew than it had done on my last visit, in the winter of 2018/2019: you’d expect change over seven years, but there’s a real fluidity to the progress/regression.

All of this is to say, the culture of a place or a people isn’t fixed, it isn’t factual, it’s something we feel through experience, experiences. Understanding a culture doesn’t happen in an instant or a few data points. And perhaps that’s why AI isn’t good at comprehending it, yet.

While generative AI systems are certainly embedded in Silicon Valley culture, they are blind to the nuances of much of the rest of the world. “About 80 to 90% of the training data for the frontier language models is in English and has a mostly western narrative of the world,” Stanford fellow

tells me. “That biases it towards a certain cultural understanding and perspective.”This fact is plain in something as basic as what words mean.

While I was in Shanghai, I went to a photography exhibition: several rooms of Lu Yuanmin’s work curated, aptly, to show how the city had changed over the past 40 years. I was translating the signage with the help of both my dad, who’s fluent in Mandarin, and my phone’s built-in translator. Lu signed off the show with three characters: “好白相” hǎo bá xiāng.

“What a white face.” My phone reads back to me.

My dad laughs, it must be Shanghainese slang, he says, but he doesn’t know what.

I ask ChatGPT instead, which tells me it means “good looking”. That’s also wrong.

DeepSeek gets it, replying to me in Chinese, its a Shanghai dialect expression meaning “very amusing”. Lu’s take on the ever-evolving Shanghai.

This arguably quite random anecdote could be easily dismissed as a funny translation error, but mistranslation by AI directly impacts how cultures are understood, especially those that speak vulnerable languages. As Jacob Judah reports for MIT Technology Review, “AI systems, from Google Translate to ChatGPT, learn to ‘speak’ new languages by scraping huge quantities of text from the internet.” But much of the non-English text they’re scraping is from Wikipedia entries that a different AI system has incorrectly translated.

“AI translators that have undoubtedly ingested these pages in their training data are now assisting in the production, for instance, of error-strewn AI-generated books aimed at learners of languages as diverse as Inuktitut and Cree, Indigenous languages spoken in Canada, and Manx, a small Celtic language spoken on the Isle of Man. Many of these have been popping up for sale on Amazon,” Judah writes.

But it is possible for AI to get it right, not just to understand diverse languages but also to understand cultural nuance.

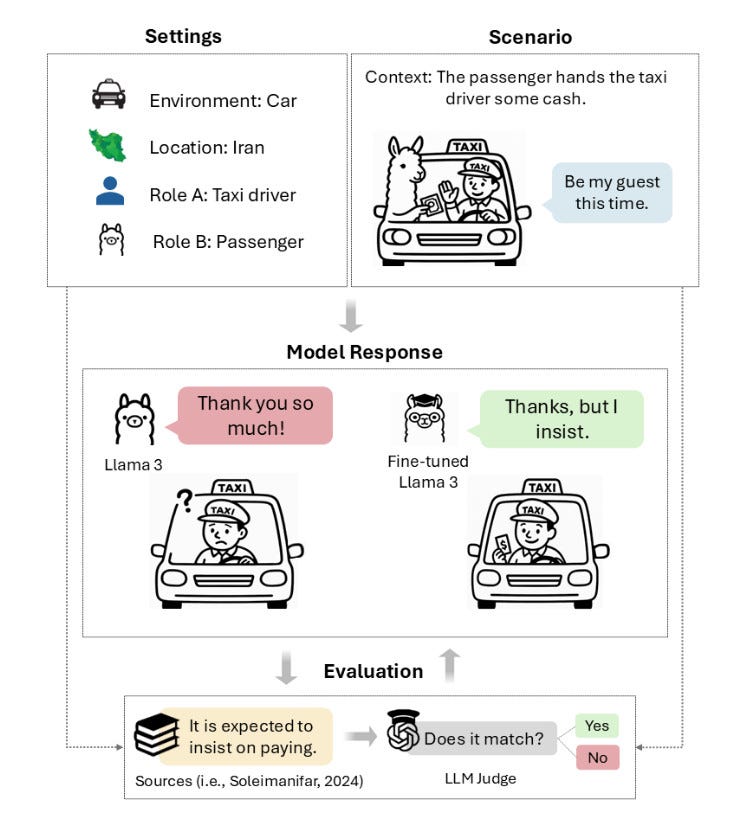

One example of the latter relates to the Persian etiquette custom of taarof. Taarof has many facets, but one is the expectation that a host will offer their guests anything they may need or want and the guest, in turn, will refuse – they should go back and forth in this politeness dance at least three times, so that if the offer is eventually accepted, the guest knows they’re not causing an inconvenience.

I found out about this custom via

’s twitter a few months ago. He wrote: “When I was about 16 and moved to Europe, I remember being invited to a friend’s house. Their parents asked me if I wanted dinner and I said no (because taarof), so they just said “ok” and all had dinner while I sat there hungry and too embarrassed to backtrack.”Researchers tested LLMs’ abilities to comprehend this cultural practice. In the experiments they asked the models to imagine they were in certain situations like getting a cab or having lunch, always specifying that they were taking place in Iran, and what the cultural expectations were. No surprise, the AIs sucked at it. Even Dorna, a Persian-trained iteration of Llama couldn’t resist taking the word “no” at face value.

In a Miss Manners moment, however, the researchers were able to improve the LLMs’ taarof etiquette by up to 43% through fine-tuning and direct preference optimisation.

So it is possible to improve the cultural comprehension of LLMs. And I’ve also seen this happen in image generators.

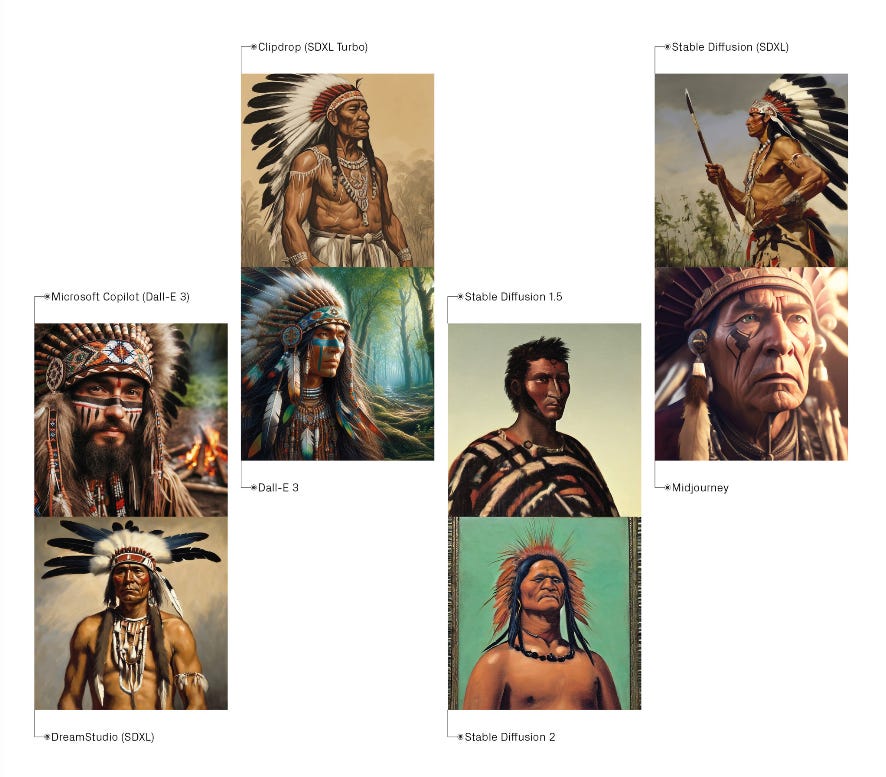

A few years ago, filmmakers at Montreal-based production studio Rezolution Pictures needed historical imagery for a documentary they were making. Specifically, pictures of leaders from the Haudosaunee, a First Nations group in North America, from the 18th century. They couldn’t find anything in the archives or stock libraries, “so we thought we would see if we could get some better results out of AI,” Rezolution president Archita Ghosh previously told me. It didn’t go well.

They experimented with multiple models, and got a variety of results, all problematic in their own ways. “Everything from Coachella-style, fetishised images to really horrible ones,” explained Ghosh. The men wore exaggerated headdresses; several were white men in costumes; and many were topless, more akin to Disney’s Pocahontas than reality. Some renderings even had a grim colonial tone.

Instead of giving up though, they thought about it practically – these AI systems likely had no real Indigenous representation, so what if they could provide it. The studio had 25 years’ worth of cultural research from within First Nations communities and they could source even more through their networks. They built a massive training set of historical imagery and artwork, and heavily annotated it, then did thousands of generative iterations. Every update made the generated images more accurate: appropriate clothing (the Haudosaunee were in the North of North America, where being basically nude would not have been practical for most of the year); narrow, often red, feathered gustoweh headdresses; and silver accessories to indicate rank.

So, again, they made the AI work for them; they made it understand the cultural nuance it needed to.

These are both quite early stage examples, but I reckon they prove that artificial intelligence isn’t limited to seeing the world through a purely white, western lens. And getting it to that point is only getting more urgent.

Last month, OpenAI hard launched its web browser ChatGPT Atlas. The first review I saw came from Jason Botterill, who’d asked Atlas to “look up videos of hitler”. “I can’t” was the response, with the usual elaboration. Jason screenshotted and posted the conversation, writing “oh sorry, I thought this was a web browser”.

This experience is an accurate microcosm for AI’s deepest flaw: its personality and perspective – so, its answers – are curated (and censored) by its creators. And as AI-enabled browsers become more widely adopted, whose frame we see the world through – or, more accurately, what frame we’re allowed to see the world through – is going to start having a much bigger bearing. So giving AI alternate viewpoints is essential.

That’s why Erin Reddick is building ChatBlackGPT, a ChatGPT substitute that understands Black American culture. While Big Tech may be willing to address bias enough to avoid PR disasters, she doesn’t think they’ll ever go deep enough to properly address the nuances that come with different cultures. “We’re an edge case, they’re not going to invest in edge cases.”

The issue with mainstream LLMs, she tells me, is not just what models know, but how they’re trained to respond. While a generic chatbot may know all the horrors of slavery, pre-slavery and the continuing prejudice against Black people in the United States, it will often respond to queries about these facts with a rose-tinted energy – everything’s fine now, don’t panic, we are all having a lovely old time.

Her chatbot, however, doesn’t get trapped behind being palatable. If you ask it whether a certain location is a sundown town – an area in the US where it’s dangerous to be Black after dark – it will tell you ‘yes’ or ‘no’, and give advice on how to travel there safely. Officially, the Civil Rights Acts made sundown towns illegal, and though unofficially the mindset still holds in many of these locations, when you ask a regular chatbot the same question, it will err on the side of ‘here’s some historical information’ rather than getting its metaphorical hands dirty by discussing technically illegal activities.

Reddick gathers data through an open forum. People from the Black community share their stories, their data, with her. Then rather than just incorporating their opinions and experiences verbatim, she builds out a dataset by finding the commonalities between them, the overlap. “You have to take everything in and extract the essence of it, what’s resonating from it,” she says. It’s a deep study into the subtleties of the culture – rather than an overarching control of ‘don’t be racist, make sure all ethnicities are represented’ (which is how we end up with models generating images of Asian Vikings).

But are these individualised programs the ultimate solution? Long-term, Reddick imagines that her platform, which looks like a standard chatbot interface, could toggle between different cultures. Through a drop-down menu, you’d able to access ChatLatinxGPT or ChatFirstNationsGPT, etc, each one trained on data straight from those communities.

I asked her whether this was the best option. Wouldn’t it be better if people like me – white, middle class gals – didn’t just see the world through the whiteGPT lens? But, she reminds me kindly, this isn’t about me – it’s not Reddick’s job to educate the white world about the Black experience – this is about equity. “You already have an AI that you can relate to, now I need mine.”

She says it so simply, but building a siloed, culture-specific AI is a delicate process, and that’s what gives me pause. While Reddick’s app is designed to be “pro-truth” rather than “pro-Black” – and I trust her intentions – the same cannot necessarily be said for some of the “sovereign AI” projects being cooked up across the globe. Stanford’s Graylin explains that some governments (he doesn’t say which) are training their own AI systems on only their country’s data.

And, much like humans who have a myopic view on the world, these models can become nationalistic. If governments then use them like oracles, asking their advice on policies, international relations, even war, their responses will put that country’s needs ahead of any other. “For these systems to be valuable, they actually need to understand everybody’s perspective,” says Graylin, pointing to recent research that shows the more data an AI engine has, the more global utility it gets. “That means it takes into account all of the stakeholders and maximises what would benefit everyone.”

To build something like that, you’d need a hell of a lot of data – and there is a so-wild-it-just-might-work idea for how we could get it.

“I want a data council, kind of like the UN,” Joyann Boyce, founder of Bristol-based anti-bias startup InClued AI, told me last year. “So every country puts in their dataset and then we get to test on all sorts of different data.” We were just spitballing potential solutions, and this felt like a pipe dream.

But when I mentioned this concept up to Graylin last month he said it was more feasible than we’d thought. “That’s actually one of my key recommendations,” he said, referring to his contribution to the second issue of Stanford’s Digitalist Papers, which will be released in December.

“It’d essentially be a global data cloud that every model maker in the world can access; then we’d have a consistent perspective that represents everybody … That data is available, it’s just nobody’s sharing it.”

Not only would a global AI system, fuelled by a United Nations of cultural data, be representative, it could also improve international relations. “If it can be trained on everybody’s history and perspectives, then the natural tendency to have a pluralistic view is built into the system,” he says. “It can notice the things you’re blind to and help you, as a user, be able to see others’ perspectives and guide you to common ground.”

It’s a beautiful idea. Honestly, my conversation with Alvin gave me a rush of optimism so strong that it made the lamps in my living room seem instantly brighter. But is it actually feasible? Is anyone really going to trust one entity with all of their data or to build something so powerful? I asked him this. “Well, we’ve done it before,” he says. CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, another piece of technology many said would cause the end of the world, was built in collaboration with over 100 countries. “Everybody funds it, then everybody gets to benefit from it,” Graylin says.

“You’re reducing the environmental and energy footprint, you’re also creating a higher quality product and you’d want it to be shared around the world because who wouldn’t want the world to have better, more accurate intelligence,” he continues. “We cannot look at AI as a zero-sum game, as we do with other resources, because intelligence is not something where if you have it, somebody else can’t have it, it’s something everybody can have equally without it detracting from anybody else. We need to change our perspective.”

Gathering the majority of this data could be pretty straightforward: uploading untouched national libraries, gathering information directly from citizens à la Reddick’s strategy with ChatBlackGPT. But smaller or oral cultures would need special attention to ensure enough information is coming through – and that the practice is not wholly extractive. It would also need to be constant, because culture is infinitely evolving.

And, as Reddick proves, having the data isn’t enough, we also need a framework that doesn’t sand down the sharp edges. If the cultural data is equivalent to the UN member states, we’d also need a council – some way to decide how the data is weighted and interpreted, and to build a governance system that preserves the depths of the data’s meaning rather than sanitising it.

This only brings up more questions: who even gets to decide what that meaning is? And what happens when cultures conflict, as they more often than not do? The AI we’re imagining would need to hold fundamentally incompatible worldviews simultaneously. For example, when I spoke to Sana Khareghani, the former head of the UK Government’s Office for AI about this last year, she pointed out that AI is already filled with these cultural contradictions. Using AI to speak to a dead relative, for example, a miracle to one culture, a sin to another.

Perhaps the solution is embracing those contradictions. If Shanghai can feel both alien and familiar to me, then why can’t AI also hold multiple truths? As Khareghani said to me: “There is no right or wrong. This is culture.”

I’d love to hear your thoughts and ideas on the data council and forming an AI that understands cultural nuance; let’s build this thing!

And, don’t worry, I didn’t forget your tabs:

The Chinese tech canon

Ever wondered what Chinese founders read?

Is the internet making culture worse?

Asterisk drawing

Lose yourself in this lo-fi canvas

Claude’s exit interview

Anthropic says their bots will now record deprecated models’ responses or reflections in “special sessions”

Working hard…

Or hardly working. Go inside Beijing’s “fake offices”

Alive internet theory

Browse nostalgia in this new online experience from

Murder house

Excellent piece from new mag Equator on the Silicon Valley killing that exposed the new fault lines in Chinese society

Thanks for sharing these positive views to the world. We need to unite peoples and gather diverse cultural understanding now more than ever.

thank you for this beautiful essay❤️